Field Manual Part 3: Are You Still Growing, Or Just Getting Better at What You Already Know?

- Charles Baker

- 2 hours ago

- 6 min read

This is the point where many otherwise capable leaders quietly plateau.

There's a question most senior leaders never think to ask themselves:

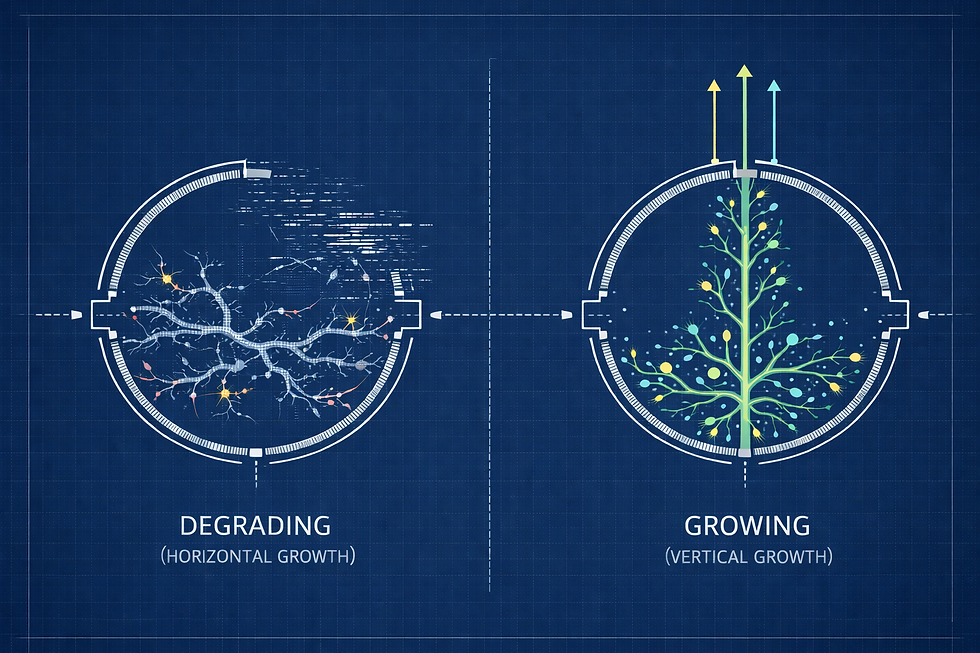

Am I expanding what I can do, or am I just getting more efficient at what I've always done?

It's an important distinction. Because at some point in every executive career, the thing that got you here stops being enough to get you there.

You weren't promoted for your potential to figure things out on the fly. You were promoted for your track record. Your pattern recognition, your technical depth, your ability to deliver results in a domain you know well.

But the roles that really stretch people aren't asking for more of the same. They're asking for something fundamentally different: the ability to think well when the problem itself is unfamiliar.

That's what growth capacity is really about.

The expertise trap

Organisations reward depth. Years in role. Technical fluency. A track record of results in a known environment. And for good reason, because that kind of expertise is genuinely valuable.

The trouble starts when the context changes.

New role. New market. Transformation. A crisis you didn't see coming. Suddenly the playbook you've relied on doesn't quite fit, and your instinct is to reach for it anyway, because it's what you know and it's always worked before.

This is the expertise trap. It's not that your knowledge becomes wrong. It's that it becomes your default, even when the situation is calling for a completely different kind of thinking.

At that point, your performance isn't limited by how smart you are or how hard you work. It's limited by your cognitive range, the variety of problem types you can genuinely engage with.

Strategy. Operations. People dynamics. Political complexity. Ethical grey areas. Unfamiliar risk. These aren't just different departments. They require different ways of thinking. And if you've spent your career deepening in one area, you may not have the mental flexibility to move between them when the role demands it.

What the research tells us (in plain language)

There's a solid body of evidence behind this, it just sits across multiple fields. Here's what it adds up to.

Experience doesn't teach you automatically

This is probably the most consistent finding in adult learning research: just having experiences doesn't mean you learn from them.

What actually drives learning isn't raw intelligence. It's what researchers call self-regulatory capacity. Things like persistence, effort, the willingness to stay engaged when something is genuinely hard, and the belief that you can actually improve.

What doesn't reliably help? Rigid planning routines, monitoring checklists, and generic reflection exercises. Growth comes from sitting with difficulty long enough that new patterns start to form. Not from ticking boxes.

This matters because a lot of leadership development puts too much emphasis on structured reflection and not enough on genuine, uncomfortable challenge.

Mental flexibility beats deep expertise when things change

People who can adapt how they think consistently outperform people who simply apply what they know, especially in unfamiliar situations.

The research is clear: transferable performance comes from understanding underlying principles, not from domain-specific knowledge. And people who've been exposed to varied, unpredictable problem types adapt faster when the rules change later, even when the new problems look nothing like what they've seen before.

In other words, exposure to novelty trains adaptability itself. Rotating between genuinely different kinds of problems does more for your future learning capacity than going deeper in a single area.

There are two kinds of expertise, and only one holds up under pressure

Routine expertise is efficient. You know the patterns, you execute well, you get consistent results in familiar conditions.

Adaptive expertise is resilient. You can adjust your thinking based on the structure of the problem in front of you, shifting between analytical and intuitive approaches depending on what the situation actually needs.

The more ambiguous and ill-defined the problem, the less reliable routine expertise becomes. And most senior roles today are full of exactly those kinds of problems.

Changing how you work is harder than learning new concepts

Here's the uncomfortable part: research on learning transfer suggests that only about ten percent of training results in sustained behaviour change back in the real world.

Transfer improves when learning is embedded in actual work, when reflection focuses on extracting principles (not just cataloguing stories), and when the environment around you actually tolerates experimentation.

Growth capacity isn't just about you. It's about the interaction between you and the system you're operating in.

IQ and EQ aren't the whole picture

We tend to think of leadership capability in terms of two things: how smart you are (IQ) and how well you read people and situations (EQ).

Both matter. IQ predicts technical proficiency and early task mastery. EQ predicts sustained performance, leadership effectiveness, and how well teams function around you. Combined, they predict more than either one alone.

But neither explains how you learn from experience or adapt to new situations.

IQ helps you understand problems. EQ helps you function within them. Growth capacity determines whether you actually get better when the problem changes.

This is why high-IQ, high-EQ leaders still stall. Growth capacity sits above both. It governs how effectively you convert what you've been through into what you're capable of next.

Why this matters more now than ever

Most senior roles today aren't stable optimisation puzzles. They're dynamic integration challenges.

You're expected to hold strategy, operations, people, culture, technology, risk, and politics in your head simultaneously, and make sound decisions across all of them.

The failure mode is almost never incompetence. It's over-reliance on a narrow slice of what's worked before.

Cognitive range becomes the differentiator when you're in a role that demands first-time thinking rather than deeper execution of familiar tasks. It's why leaders with varied career paths often outperform specialists when the context shifts. Not because they know more, but because they've learnt how to learn across domains.

How to actually expand your range

The evidence points to a few principles that hold up consistently.

Variation beats volume. Repeating similar work makes you more efficient, but it doesn't expand your range. Seek out qualitatively different kinds of problems, not just more of the same.

The challenge has to be real. Simulated exercises without genuine stakes rarely transfer. Growth requires something meaningful to be on the line.

Extract principles, not just stories. The leaders who grow fastest don't just collect experiences. They pull out transferable lessons that apply across contexts. "What's the underlying pattern here?" is a more useful question than "What happened last time?"

Stay in the game. Persistence, effort, and a genuine belief that you can improve matter more than talent or technique. Growth comes from staying engaged with difficulty, not from finding shortcuts around it.

Your environment matters. If the system around you punishes experimentation or only rewards short-term optimisation, your cognitive range will shrink, no matter how committed you are to expanding it.

What this means for you

Expanding your cognitive range isn't about abandoning your expertise. It's about making sure your expertise doesn't become the only lens you look through.

Leaders with high growth capacity deliberately seek out situations that force different kinds of thinking. They move between strategic, operational, and people challenges. They lean into ambiguity instead of avoiding it. And when they notice their default responses aren't working, they adjust rather than doubling down.

They don't confuse feeling comfortable with being competent.

If you've been in a similar kind of role for a while and you're performing well, that's worth celebrating. But it's also worth asking: Is this role still stretching me? Am I learning new ways to think, or am I getting more polished at the ways I already think?

The leaders who keep scaling are the ones who keep expanding their range. Deliberately, consistently, and often uncomfortably.

The bottom line

Expertise tells you what worked before. Cognitive range determines whether you can adapt when it no longer does.

Growth capacity is not about being smarter, more charismatic, or more self-aware in the abstract. It is about how effectively you convert experience into future capability, especially when the terrain is unfamiliar and the stakes are real.

That is what separates leaders who keep scaling from those who quietly plateau.

And while no one can expand your cognitive range for you, the right coaching environment can make that expansion faster, more deliberate, and far more likely to hold under pressure.

That is not a luxury for senior leaders.

It is a structural requirement of modern leadership.

Comments