Field Manual, Part 1: Learning Agility – The Capability That Determines Leadership Growth

- Charles Baker

- 19 hours ago

- 7 min read

Most leadership plateaus are not caused by a lack of effort, intelligence, or ambition.

They are caused by a learning breakdown.

As leaders move up, the job quietly changes. What once rewarded execution and expertise begins to demand judgement, adaptation, and decision-making without clean feedback. At that point, what matters most is not what a leader knows, but how effectively they learn.

That is where learning agility enters the picture.

What learning agility actually means

The most robust definition of learning agility comes from Lombardo and Eichinger, who originally coined the term. In later empirical work, it is defined as:

The willingness and ability to learn from experience, and subsequently apply that learning to perform successfully under new or first-time conditions.

This definition matters because it describes a process, not a trait in isolation.

Two elements are inseparable.

First, learning from experience.This is the capacity to extract the right lessons from past situations. Not just what happened, but why it happened. What assumptions were wrong. What signals were missed. What patterns actually mattered.

Second, application to novelty.This is the transfer function. Can those lessons be carried forward into unfamiliar contexts where old playbooks no longer apply?

Highly learning-agile leaders do not merely accumulate experience. They convert it into better judgement.

Why researchers call it a metacompetency

Learning agility is often described in the research as a metacompetency.

That word is precise.

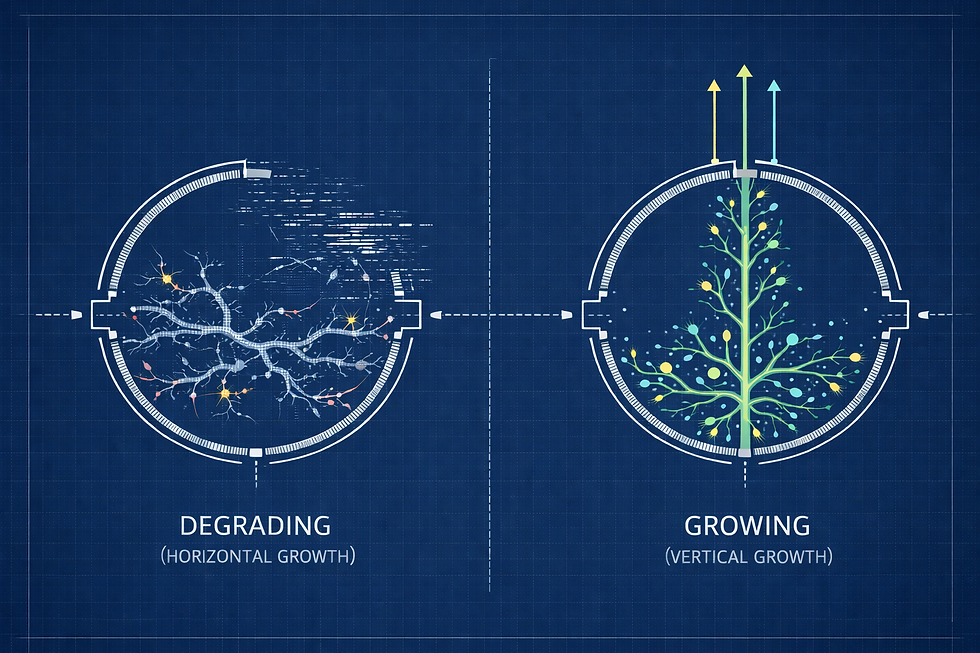

A metacompetency sits upstream of other skills. It determines whether those skills can be developed, adapted, or upgraded over time.

This explains a familiar leadership paradox.

Two leaders with similar intelligence, experience, and track records are promoted into more complex roles. One continues to grow. The other slowly stalls. The difference is rarely effort or intent. It is how each leader metabolises experience.

When learning agility is high, other competencies evolve.When it is low, even strong capabilities plateau.

The evidence is unusually strong

Leadership research is full of soft constructs. Learning agility is not one of them.

Across multiple field-based meta-analyses, learning agility shows strong relationships with both leader performance and leader potential. It has also been shown to outperform job performance alone when organisations attempt to identify future high-potential leaders.

That matters, because performance tells you what someone did in a known system.

Learning agility tells you what they are likely to do when the system changes.

The four dimensions that drive learning agility

Learning agility is not a single trait. It is typically assessed across four dimensions.

Mental agility The ability to think through problems from multiple angles, tolerate complexity, and reframe issues when old models stop working.

People agility The capacity to work effectively with different personalities, cultures, and power dynamics, while remaining open to feedback.

Change agility An appetite for novelty. Seeking new challenges, experimenting rather than protecting certainty, and staying curious during disruption.

Results agility The ability to deliver outcomes even when conditions shift, priorities collide, or resources are constrained.

Together, these explain why learning agility predicts future success more reliably than past performance alone.

What learning agility is not

It is tempting to equate learning agility with learning speed.

The research does not support that.

There is no standalone construct called “learning speed” that predicts leadership growth. What looks like speed is usually something else: shorter learning cycles.

Leaders with high learning agility seek feedback earlier, reflect more honestly, and adjust faster. Leaders with low learning agility may process information quickly, but update their behaviour slowly because identity, status, or prior success makes them harder to shift.

Speed is a by-product. Agility is the mechanism.

The question leaders eventually ask

If learning agility matters this much, the obvious question follows.

Can it actually be developed, or is it something you either have or do not?

The research is clear on this point.

Learning agility reflects both relatively stable individual differences and a set of learnable behaviours and strategies. While certain personality traits linked to learning agility may be harder to change, many of the behaviours that drive it can be deliberately built.

That distinction changes everything.

How learning agility is actually built

1. Stretch that forces adaptation

The strongest driver of learning agility development is experience, but only when that experience stretches current capability.

Learning accelerates when there is a meaningful gap between what a leader knows how to do and what the situation demands. Comfortable roles do not produce agility. Productive mismatch does.

Research shows that high-performing executives consistently describe challenging assignments as their most important developmental experiences, particularly early exposure to roles requiring judgement rather than execution.

The lesson is simple. Growth follows stretch, not tenure.

2. Coaching that shortens learning cycles

Coaching plays a critical role in accelerating learning agility.

Not because coaches provide answers, but because they speed up how leaders extract and apply lessons from experience.

Effective coaching develops specific behaviours linked to learning agility: noticing what is actually happening, experimenting rather than defending certainty, actively seeking feedback, reflecting on assumptions, and regulating emotion so learning is not blocked by defensiveness.

This is why coaching matters most during transitions, ambiguity, and role expansion. Those moments determine whether leaders update their mental models or reinforce the wrong ones.

3. Environments that reward learning, not just correctness

Learning agility does not develop in punitive environments.

Organisational culture plays a decisive role. Supportive, psychologically safe, and growth-oriented cultures foster learning agility. Blame-driven cultures suppress it.

Leaders learn faster when they can admit uncertainty, test ideas, receive feedback without humiliation, and be wrong early rather than catastrophically late.

Cultures that only reward flawless execution quietly train leaders to stop learning.

4. The three personal inputs that feed learning agility

Research consistently highlights three individual factors that support learning agility and can be developed over time.

Diverse experience Varied career paths increase learning agility by forcing comparison, transfer, and pattern recognition.

Self-awareness Leaders who can observe their own behaviour and tolerate feedback are far more likely to convert experience into growth.

Comfort with complexity Learning agility thrives when leaders can hold competing ideas and resist premature closure. This capacity can be developed through exposure and reflection.

None of these require changing personality. They require changing what leaders pursue and how seriously they examine themselves within those experiences.

The uncomfortable implication

If learning agility can be developed, then many leadership failures are not mysterious.

They are signals that leaders were never placed into real stretch, never taught how to learn from experience, or never supported by environments that allowed learning to happen.

It is a system design problem.

The organisations that scale leadership effectively will not be the ones that find the rare “naturally agile” few. They will be the ones that deliberately engineer learning agility at scale.

And the leaders who keep getting better will not be the fastest learners in the room. They will be the ones who most relentlessly turn experience into better judgement.

The questions below are intended as a reflective exercise. They are designed to slow thinking down, create distance from day-to-day performance, and help you notice how you actually learn from experience over time.

Questions that reveal learning agility (or its absence)

1. Experience → Insight

These questions test whether experience is actually being converted into judgement.

What is something I strongly believed twelve months ago that I no longer believe?

Which recent decision would I make differently now, and what exactly changed my thinking?

When something goes wrong, do I default to explaining it, or examining it?

What patterns keep repeating in my leadership that I have not yet disrupted?

Low learning agility often shows up as repetition with better justification.

2. Feedback metabolism

These questions reveal how well feedback is absorbed, not just received.

Who gives me feedback that genuinely changes my behaviour?

When was the last time feedback surprised me?

What feedback do I routinely discount, and why?

Do I seek feedback early, or only once outcomes are obvious?

Highly learning-agile leaders do not just tolerate feedback. They pull it forward.

3. Adaptation under pressure

Learning agility shows itself most clearly when stakes are high.

What do I default to when I am under real pressure?

In stressful situations, do I get more curious or more certain?

When the context shifts, how long does it take me to notice that my old playbook no longer fits?

What signals do I tend to ignore until it is too late?

Pressure does not destroy learning. It reveals its limits.

4. Stretch and exposure

These questions surface whether growth is intentional or accidental.

When was the last time I chose an assignment where I was not immediately competent?

Am I optimising for success, or for learning?

Where in my role am I too comfortable?

If my role stayed exactly the same for the next two years, what would I stop learning?

Learning agility decays fastest in roles that reward predictability.

5. Identity and defensiveness

This is where learning agility usually breaks.

What parts of my identity make it hard for me to change my mind?

Where do I confuse confidence with correctness?

What do people hesitate to challenge me on?

What would I need to let go of to grow into the next level of leadership?

Leaders rarely fail because they cannot learn. They fail because something feels too expensive to unlearn.

If you've come this far then you deserve a real corker of a question to finish on. I personally feel that this single diognostic question matter more than all the others -

What would have to be true for my current way of leading to be wrong?

Leaders with high learning agility can answer that question clearly.

Leaders with low learning agility struggle to answer it at all.

How to use these questions properly

These are not journaling prompts to be completed once and forgotten.

They work best when:

revisited every 6–12 months

discussed with a coach or trusted peer

paired with real decisions, not abstract reflection

Learning quality is not revealed in what a leader says, It is revealed in what they change.

Comments