Field Manual Part 2: Feedback Metabolism & Integration

- Charles Baker

- 14 hours ago

- 5 min read

Stop Defending, Start Growing.

Most leaders claim they are open to feedback.

The claim, on its own, is almost meaningless.

The real question is not whether feedback reaches a leader. It is whether it survives the journey inward,

whether it is processed, tolerated, and ultimately converted into changed behaviour, particularly when it threatens identity, status, or the story a leader has built about their own competence.

During leadership transitions, this distinction becomes decisive.

Feedback does not fail. Metabolism does.

The evidence is uncomfortable

Decades of research reveal an inconvenient pattern.

Feedback produces only modest behavioural change, with extreme variability across individuals. Roughly half of leaders improve in observable ways. A significant proportion show no change at all, and a non-trivial minority actually deteriorate.

This is not because the feedback was unclear or poorly intentioned. It is because feedback is not, at its core, a message problem.

It is a metabolic one.

Two leaders can receive identical feedback, from the same source, at the same moment. One adapts. The other rationalises. The difference between them is not intelligence or motivation. It is what happens internally in the seconds after discomfort appears.

Why integration amplifies the problem

The first six to twelve months in a new role are uniquely hostile to learning.

Feedback arrives before trust has been established and before context is fully understood. It tends to be indirect, emotionally loaded, and shaped by political risk. People hedge. They soften. They hint rather than state.

Leaders with strong feedback metabolism treat this ambiguity as part of the signal. Leaders with weak feedback metabolism treat it as grounds for dismissal.

This is precisely how integration failures begin, quietly, long before performance problems become visible.

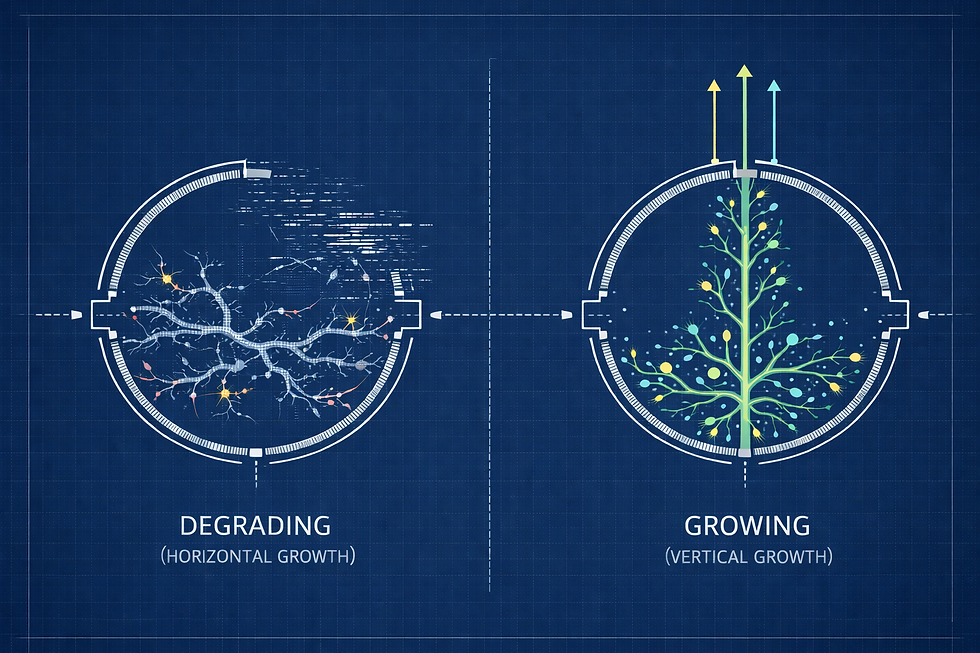

What feedback metabolism actually means

Feedback metabolism is not about being "open" or "humble."

It is the capacity to move through four distinct stages without becoming stuck.

Contact with discomfort. The feedback threatens self-image, competence, or the narrative the leader has constructed about who they are.

Toleration without defence. The leader resists the reflex to explain, correct, or contextualise prematurely.

Reflection over time. The feedback is revisited once emotion settles and patterns become clearer.

Behavioural conversion. Something observable changes in how they lead, not merely in how they think.

Most leaders never make it past stage two. They relieve discomfort by explaining, and in doing so, foreclose on learning.

The diagnostic question that cuts through polish

"Tell me about feedback you initially rejected but later realised was right."

This question works because it exposes the process, not the outcome.

High Growth Capacity leaders describe:

Irritation, defensiveness, or embarrassment at the point of contact

Time passing before understanding emerged

Repetition or consequence that made the pattern undeniable

A concrete shift in behaviour, not just in mindset

Low Growth Capacity leaders:

Critique the accuracy of the feedback itself

Focus on delivery rather than substance

Describe insight without offering evidence of change

Subtly cast themselves as the reasonable party and the feedback as flawed

They received the feedback. They did not metabolise it.

Why emotion blocks learning

Feedback that matters almost always triggers emotion. This is not a deficiency, it is biology.

Threat narrows attention. Defensiveness reduces curiosity. Self-protection quietly becomes the priority, displacing the openness that learning requires.

Leaders who grow are not less emotional than those who stagnate. They are better at staying regulated long enough for learning to occur. They do not rush toward resolution.

They allow ambiguity, irritation, and uncertainty to sit, without acting them out.

That pause, uncomfortable as it is, is where learning begins.

Power quietly distorts feedback

As authority increases, the quality of feedback degrades.

People say less. They delay honesty. They manage impressions, not because they are dishonest, but because the cost of candour rises with every rung of the hierarchy.

Over time, leaders begin to confuse silence with alignment and compliance with commitment. The two are not the same, but from inside a position of power, they can feel indistinguishable.

Leaders with strong feedback metabolism assume information is missing. Leaders with weak feedback metabolism assume information is complete.

Only one of those assumptions is safe.

Weak signals are where learning actually starts

Organisational failure almost never announces itself clearly.

It begins with repeated friction, low-level disengagement, concerns expressed sideways rather than upward, and patterns that feel inconvenient rather than urgent. Hierarchies are remarkably efficient at filtering these signals out before they reach the people who most need to hear them.

Leaders who wait for crisp, well-articulated feedback are already late. Growth-capable leaders train themselves to notice what is consistently present but softly expressed.

Weak signals are not noise. They are early indicators, and often the only warning a leader will receive.

Reflection is not insight. It is time.

One of the most damaging myths in leadership development is the idea of instant insight — the belief that understanding arrives whole and immediate.

Real change is delayed.

Leaders often reject feedback initially, then recognise its validity weeks or months later, once emotion has faded and patterns have had time to accumulate. Genuine reflection requires psychological space, a willingness to revisit the signal more than once, and the discipline to resist premature closure.

Feedback that "lands immediately" is rarely the feedback that changes behaviour. The feedback that transforms is the kind that lingers, unsettled, until it can no longer be ignored.

Why self-reported learning is unreliable

Most leaders can articulate what they have learned. That tells you remarkably little.

Self-reported insight routinely diverges from observable behaviour. People often feel more changed than they actually are, a gap that widens the more senior and insulated they become.

This is why effective integration assessment focuses on what others notice changing, not on what the leader claims to understand.

Awareness is internal. Change is public.

Active feedback seeking changes the game

Leaders who grow do not wait for feedback to arrive. They design loops.

They choose credible sources. They ask specific, targeted questions. They follow up and close the loop visibly, creating the conditions under which honesty becomes less costly for those around them.

This discipline improves signal quality and lowers the social risk of candour, a combination that compounds over time.

Passive leaders receive feedback only when the system forces it upon them. Active leaders pull learning forward, before the organisation has to push.

What you are really assessing

When you ask feedback questions, you are not testing character. You are testing capacity.

Can they describe discomfort without defending against it? Can they tolerate delayed understanding rather than rushing to certainty? Is there evidence of changed behaviour — not just claimed insight? Do they actively engineer feedback loops, or do they wait passively for the truth to find them?

This is Growth Capacity under real operating conditions.

Why this matters more than competence

Technical skill gets leaders appointed.

Feedback metabolism determines whether they integrate, adapt, and endure.

In modern organisations, where signals are weaker, feedback is more politically filtered, and consequences are increasingly delayed, the leaders who prevail are not the smartest in the room. They are the fastest learners under distortion.

Self-reflection questions for leaders

These are not designed to feel comfortable.

What feedback have I dismissed too quickly in the past year?

Who gives me feedback that genuinely changes my behaviour, and what is it about them that makes it land?

What pattern of feedback do I keep hearing but have not yet acted on?

How do I typically respond in the first twenty-four hours after receiving threatening feedback?

What behaviour have I tangibly changed as a direct result of feedback recently?

Where might silence be masking misalignment or fear?

What feedback loops have I deliberately engineered, rather than passively received?

If these questions feel irritating or confronting, feedback metabolism is already under strain.

Comments